Erasmus+

“This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein”

Psychological intervention of the injured wrestler

Upon completion of this module the reader will be able to:

present a case of an injured athlete with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear diagnosis who implied simple mental preparation techniques during preoperative and postoperative season in order to deal with pain and other negative feelings

First, it is strongly suggested to review

Module 6: Counseling fostering success WATCH

One of the great dangers an athlete can face, if not the greatest, is the risk of getting injured. That’s why its prevention and treatment constitute an essential part of the medical and performance department of the clubs. However, a part not yet explored about this risk has to do with the athlete’s psychological and social factors.

According to Andreas Ivarsson, PhD in psychology at the University of Halmstad, in Sweden, and Head of Psychology and personal development at Arsenal F.C., there are a few main mechanisms for the relationship between stress and injury risk. One of these is that stress will negatively influence the athlete’s abilities to take high qualitative decisions due to a narrowed peripheral vision. Another proposed mechanism is that stress is likely to generate higher levels of psychophysiological fatigue. An increase in fatigue might, in turn, increase the risk of becoming injured.

Read carefully the description of these techniques as they can also be used by healthy athletes for injury prevention.

Ivarsson, A., Johnson, U., Karlsson, J., Börjesson, M., Hägglund, M., Andersen, M. B., …Waldén, M. (2018). Elite female footballers’ stories of sociocultural factors, emotions, and behaviors prior to anterior cruciate ligament injury. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Advance online publication.

How can mental preparation help the injured athlete during the first steps of rehabilitation? A case of an athlete with ACL tears diagnosis.

The athlete of the present case report was a 25 year old wrestler athlete. The program that is described below was applied by the specialists of the rehabilitation team: physical therapist, sport psychologist, athletic trainer and physician. Rehabilitation goals and mental preparation are described for each season, preoperative and postoperative.

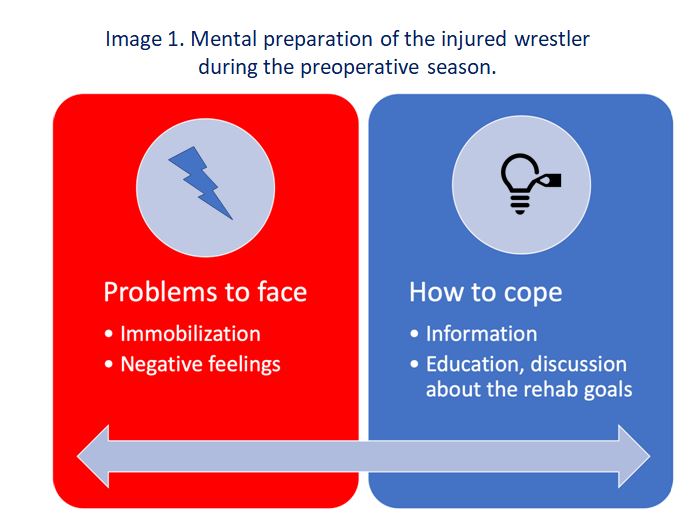

Phase 1: Preoperative season

Rehabilitation goals

The initial goals of rehabilitation were to reduce swelling, return knee range of motion and restore normal gait pattern. The time needed to accomplish these goals was 3 weeks. To reduce swelling, a cold compression cuff (Cryo/Cuff) has been applied to the knee and filled with ice-cold water. The athlete was wearing the cuff continually except when walking.

Mental preparation

After the arrival of the athlete, a personal interview, took place. During the procedure of the interview, physical therapist, athletic trainer and the sport psychologist were present. The athlete revealed negative feelings such as fear, anger, loss of confidence and depression. After the end of the procedure, the specialists decided that the athlete needed to learn a relaxation technique and the mental imagery (as described in the passages below) and to be educated about the characteristics of the injury.

The physician educated the athlete about the characteristics of the injury, surgery and rehabilitation goals. Knee anatomy and ACL function have been carefully explained before surgery. Once surgical reconstruction was elected, the rehabilitation goals and their rationale were discussed. A booklet covering the same information was given to the athlete to review at home

Phase 2: Post-operative season

Postoperative rehabilitation consisted of two parts: The first part of rehabilitation focused on returning the knee to a quiescent state by eliminating hemarthrosis and pain while achieving full knee motion. The second part of rehabilitation involved donor-site strengthening, first with full flexion exercises to pull the patellar tendon to length, then with repetitive strengthening exercises to stimulate tendon growth.

Rehabilitation goals

Exercises for regaining full range of motion begun the day of surgery. Hyperextension was maintained with 10 minutes of heel prop exercises every waking hour. Flexion exercises were performed six times daily. This could easily be done by slowly increasing flexion of the CPM machine to the point of tightness and holding the position for several minutes. Once maximal flexion has been attained in the CPM machine, the athlete performed heel slide exercises with the leg out of the CPM machine. Leg control exercise was also started on the day of surgery and consisted of quadriceps contraction exercises and independent straight-leg raises. Weight bearing was allowed as tolerated, but the athlete was generally instructed to restrict walking.

The goals for the remainder of phase 2 were the same as during the immediate postoperative period: control swelling, maintain hyperextension, increase knee flexion to at least 110degrees, and establish good leg control. Progress toward these goals was evaluated one week after surgery at the first postoperative visit.

Mental preparation

a. Education about pain

First, the physical therapist educated the athlete about what to expect and described the feeling that he is likely to experience while doing the necessary range of motion exercises. Expressions such as, “don’t be surprised if you feel a little tenderness on the inside of your knee” prepared the athlete for what he expected. As the rehabilitation progressed, the therapist assisted the athlete distinguish between that pain associated with healing and that pain which may signal further injury: “You might feel some tightness in the inside of your knee as you rotate it, but that’s good because you need to stretch it out”.

- Progress recording and goal setting

Second, the therapist recorded the athlete’s progress. As long as the athlete was seeing his improvement, he was setting a goal about his next trial (1). For example, the therapist was measuring the knee range of motion and informed the athlete that he had already gained 90 degrees of dorsi flexion. Then he was asking him to think “I have my knee flexed at 90 degrees. I will try again to obtain a flexion of 95 degrees” and so he tried again.

- Relaxation

Considering the fact that muscular tension -caused by anxiety- usually increases sensations of pain, specialists educated the athlete to apply a relaxation technique before the therapeutic session, focusing particularly on muscles involved (knee extensors and flexors).

First the athlete learned the importance of “breathing” sitting in a quiet room in a comfortable position (2). Then, the athlete was introduced to the “progressive relaxation” technique (3) in order to feel the tension in the muscles followed by their relaxation (4).

d. Mental Imagery

Finally, the sport psychologist introduced mental imagery (5,6). Initially, the researcher had the athlete in a quiet room where with his eyes closed tried to imagine the knee, to fully execute the exercise program on the machine, with no restrictions. After the athlete could visualize very clearly this whole procedure, he did the same while he was doing the actual rehabilitation program (working with the CPM machine). Additionally, mental imagery helped the athlete create an image of the injured area being healed and mended.

Bibliography and the additional learning materials

Conclusion

The athlete teamed up with the specialists with success and showed consecutive motivation throughout the rest of the rehabilitation period. He completed with success his physical preparation with joint stability exercises and wrestling related skill training using always the mental preparation techniques that he was taught in the beginning.

- MALLIOU P, BENEKA A, AGGELOUSIS N, THEODORAKIS Y. Goal setting: An efficient way to maximise isokinetic performance. Isokinetics and Exercise Science, 1998:7:11-17

- DAVIS M, ESHELMAN E, McKAY M The relaxation & stress reduction workbook. New Harbinger Publications, Inc. Oakland, 1998

- JACOBSON E. Progressive relaxation. Chicago University Press, 1938

- MARTENS R. (1987). Coaches guide to sport psychology. Champaign IL. Human Kinetics.

- Weinberg R. S. (1982). The relationship between mental preparation strategies and motor performance: A review and critique. Quest, 1982; 33, 195-213.

- CONN P. Preperformance routines in sport: Theoretical support and practical applications. Sport Psychologist, 1990; 4: 301-312.

[ays_quiz id=’36’]

Erasmus+

“This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.”